In a noteworthy neuroscience experiment in the U.K., researchers caught sight of a fascinating phenomenon. Until then, scientists assumed the wave of electrical activity in the brain (that signals visual processing is taking place) would remain constant when the visual stimuli on display remained static.

However, the experiment revealed that when the context in which the visual content was presented changed, the electrical brainwave activity across a variety of cortical regions increased, despite the fact that the visual stimuli remained unchanged.

In other words, by merely changing the viewer’s expectations of what they should be looking at (subjects were looking at an assortment of bottles where the only change made was the question posed about the image), researchers were able to alter a person’s cognitive interpretation of visual input.

With this neural evidence at hand, scientists had finally peered into the brain’s magic box of perception and caught a glimpse of how contextual or structural cues influence how we interpret sensory stimuli, which in turn builds our very real sense of place.

The question is by no means a rhetorical one nor is it the purview of self-styled futurists or VR developers. The question is central to architects, designers, facility planners and more so to environmental design researchers striving to uncover the attributes of interior design that have the greatest impact on health, productivity, and wellbeing.

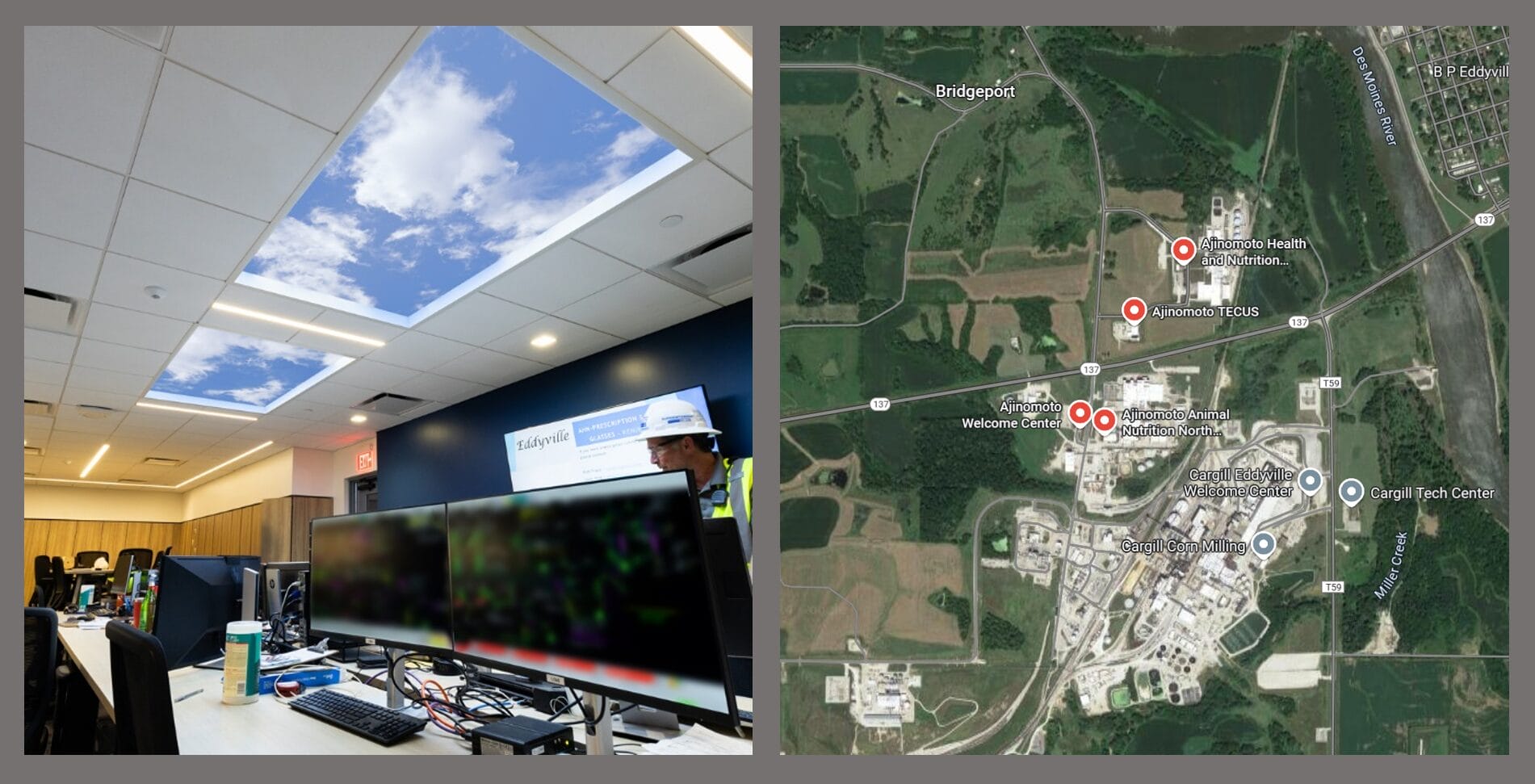

Along this line of inquiry, Real vs Simulated Nature research has thus far ignored contextual cues when setting out to compare the restorative value of genuine views to nature versus simulated ones.

To learn more about the implications of architectural context, see our two-part series, Simulated Nature Research Gets Real Part 1 and Part 2.